You’ll find Enfield’s remnants beneath Massachusetts’ Quabbin Reservoir, where this once-thriving mill town stood for 250 years before its deliberate flooding in 1938. Originally settled by John and Robert Pease in 1679, Enfield grew into a bustling community of 2,500 residents with fourteen mills, shops, and a railroad connection. Boston’s expanding water needs led to the town’s controversial disincorporation, forcing residents to relocate and leaving behind a fascinating tale of sacrifice and transformation.

Key Takeaways

- Enfield was a thriving Massachusetts town with 2,500 residents that was deliberately flooded in 1938 to create the Quabbin Reservoir.

- The town featured a bustling center with a Congregational Church, town hall, shops, and fourteen local mills for textiles and wood products.

- Boston’s expanding population and water needs led to the Swift River Act of 1927, forcing residents to relocate through eminent domain.

- Before flooding, the town was systematically dismantled, with buildings demolished and residents’ ancestors’ remains relocated to Quabbin Cemetery.

- Historical remnants include submerged cellar holes, granite steps, and memorial markers, with annual remembrance events preserving Enfield’s legacy.

Early Settlement and Town Origins

Before European colonization transformed the landscape, Indigenous peoples thrived in the area that would become Enfield for thousands of years, leaving behind archaeological evidence of their presence through arrowheads and village sites. Dutch explorer Adriaen Block made first European contact with Native Americans there in 1614 along the Connecticut River.

The area’s transformation began when John Pynchon built a sawmill in 1674, though it was destroyed during King Philip’s War the following year. One notable archaeological discovery includes varved clay deposits that provide evidence of ancient Glacial Lake Hitchcock’s presence in the region.

Early settlers John and Robert Pease arrived from Salem in 1679, weathering their first winter in a hillside shelter. By 1680, about 25 families had joined them, forming a “Salem Colony.” The settlers were required to establish a church and provide support for a minister as conditions of their land grant.

Indigenous interactions culminated in 1688 when settlers purchased the land from Notatuck, a Podunk native, for 25 pounds Sterling.

Life in Pre-Reservoir Enfield

As you’d walk through pre-reservoir Enfield, you’d find a town center anchored by the Congregational Church, town hall, and various shops serving the community’s daily needs.

The Bethel Masonic Lodge, general stores, and artisan workshops lined the streets, while farms dotted the surrounding countryside where most residents earned their living. The Swift River Company operated as the economic backbone of the community, creating a company town atmosphere in Smiths Village from 1821 until 1935.

Religious and cultural life centered around the church, library association, and civic organizations like the Daughters of the American Revolution, which hosted regular gatherings until the town’s dissolution in 1938. The community faced a heartbreaking transition when 2,500 residents were displaced during the reservoir’s creation.

Town Layout and Buildings

The historic town of Enfield stood proudly at the confluence of the Swift River‘s east and west branches in western Massachusetts, serving as the largest and southernmost of the four towns later sacrificed for the Quabbin Reservoir.

As the waters of the Quabbin Reservoir rose, the once-thriving community was submerged, leaving behind remnants of a forgotten past. Today, the ghost towns of Massachusetts serve as haunting reminders of the lives and stories lost to progress. Exploring these areas offers a glimpse into the rich history that shaped the region, where nature and memory intertwine.

The town layout featured wood-frame houses scattered along main roads and riverbanks, with a vibrant town center that included a town hall, Congregational church, and school buildings.

You’d have found farms dotting the landscape, complete with barns and outbuildings, while small mills and artisan shops lined the waterways. These thriving industries included fourteen local mills producing textiles, hats, and various wood products.

Essential infrastructure included a firehouse, post office, and library, all connected by roads that linked to neighboring townships.

The Boston and Albany Railroad‘s Athol Branch served the community until the reservoir’s creation forced its abandonment. In April 1938, Enfield and its neighboring communities were officially disincorporated to make way for the new reservoir.

Daily Community Activities

Life in pre-reservoir Enfield revolved around a vibrant mix of agricultural pursuits and community engagement.

You’d find families working their farms from dawn till dusk along Long Hill Road, tending crops and livestock through the changing seasons. When work was done, you’d join your neighbors at community gatherings, dances, and baseball games where locals mingled with reservoir construction engineers. The devastating reality hit when the town held its final Farewell Ball in 1938.

Your daily routine might include shopping at local stores for supplies, sending children to the town school, or trading farm goods with nearby communities. Today, visitors can learn about these lost communities at the Visitor Center displays.

Recreational activities brought everyone together through jazz bands, hiking, and picnicking. Even during the challenging times of reservoir construction, you’d maintain strong social bonds through shared activities at schools, parks, and town halls, preserving the tight-knit spirit that defined Enfield’s community.

Religious and Cultural Life

Within pre-reservoir Enfield’s spiritual landscape, you’d find the Congregational Church standing as the town’s religious and cultural cornerstone, where weekly services merged seamlessly with community gatherings and political discourse.

You’d witness church gatherings that shaped community identity through education, with 271 students enrolled across eight districts by 1854. The Bethel Masonic Lodge and Daughters of the American Revolution complemented religious life, fostering a blend of patriotic and spiritual connections.

Built in 1787 on Captain Hooker’s land, the Congregational Church served as a testament to the town’s deep religious roots.

- Walking into the town library, you’d discover 2,000 volumes reflecting moral and religious teachings.

- You’d experience traditional festivals where spiritual and civic life intertwined.

- You’d see charitable works flowing from religious conviction.

- You’d join neighbors at the 1938 Farewell Ball, singing hymns of remembrance.

- You’d find comfort in pastoral care that extended beyond Sunday services.

The final community gathering in April 1938 brought together locals and outsiders alike for a poignant last farewell ball, marking the end of an era before the town’s submersion.

The Decision to Build Quabbin Reservoir

By the 1920s, you’d have witnessed Boston’s existing water supplies reaching their limits as the metropolitan population swelled beyond the capacity of current reservoirs.

The Massachusetts General Court responded to this crisis by passing Chapter 375 of the Acts of 1926, which established a special metropolitan district water supply commission with broad powers to create what would become the Quabbin Reservoir.

You would’ve seen this watershed project designed to serve Boston and roughly 40 surrounding communities, marking a decisive solution to the region’s growing water security concerns.

Growing Water Supply Needs

As Boston’s population surged in the early 20th century, city planners faced an increasingly urgent water crisis that would reshape western Massachusetts forever.

The existing water sources, including Wachusett Reservoir, couldn’t sustain the growing metropolis. You’re looking at a time when water scarcity threatened both public health and industrial growth, as population pressures pushed the system to its limits.

- Your city was expanding faster than anyone imagined, with millions needing clean water daily.

- The water you depended on was becoming dangerously scarce as urbanization accelerated.

- Your local rivers and reservoirs were proving inadequate for the region’s future.

- Your industries and homes required a solution that would last generations.

- Your community’s survival hinged on finding a massive new water source.

The Swift River Valley emerged as the answer, leading to plans for what would become the Quabbin Reservoir.

Political and Public Response

The Massachusetts legislature’s passage of Chapter 375 in 1926 set in motion one of the state’s most controversial public works projects – the creation of Quabbin Reservoir.

You’ll find that political tensions emerged immediately, with Connecticut filing legal challenges over water rights that weren’t resolved until a 1931 Supreme Court ruling favored Massachusetts.

The project’s human toll was staggering. If you’d lived in Dana, Enfield, Greenwich, or Prescott, you’d have been among 2,500 residents forced to relocate as these towns faced disincorporation in 1938.

While some residents in Dana voted to surrender their lands, public sentiment was complex. The systematic evacuation lasted nearly two decades, requiring home demolitions, grave relocations, and the dissolution of long-standing community institutions – all in service of Boston’s growing water needs.

Relocation and Displacement of Residents

Under the Swift River Act of 1927, approximately 2,400 residents from the towns of Dana, Enfield, Greenwich, and Prescott faced mandatory displacement to make way for the Quabbin Reservoir project.

The state’s use of eminent domain forced you to sell your property, often below market value, with no assistance for finding new housing or employment. This displacement trauma tore apart communities that had existed for generations, destroying your community identity and longstanding social networks.

- You watched as your neighbors’ homes were either demolished or physically relocated.

- Your local businesses received no compensation, devastating the local economy.

- Your ancestors’ remains were exhumed from cemeteries and moved to Quabbin Cemetery.

- Your town’s official existence ended on April 27, 1938.

- Your community scattered to surrounding areas with no formal support system.

Final Days of a Vanishing Town

During the final months before Enfield’s disincorporation in April 1938, your once-vibrant community underwent systematic dismantling to prepare for the Quabbin Reservoir project.

You’d witness town offices closing one by one as the School Committee and Overseers of the Poor ceased operations. Local churches, Masonic lodges, and the library association either shut down or relocated, severing generations of emotional bonds.

The landscape you once knew transformed dramatically as crews demolished buildings, burned structures, and cleared every tree from the Swift River Valley.

Railroad tracks were torn up, roads were rerouted, and the valley was stripped bare. This profound community loss affected approximately 2,500 residents who were forced to abandon their lifelong homes, watching as their tight-knit society dissolved into memory.

Engineering the Reservoir Project

Before engineers could begin constructing the massive Quabbin Reservoir, extensive soil testing and geological surveys throughout the Swift River Valley established the project’s foundation.

The engineering challenges required diverting the Swift River using temporary cofferdams, allowing crews to work on dry land. Construction techniques focused on building the Windsor Dam with precisely compacted earth-fill layers, sealed to bedrock with concrete for maximum stability and minimal seepage.

- You’d witness the displacement of entire communities as 60,000 acres were acquired for the project.

- You’d see miles of railroad tracks abandoned and rerouted around the future reservoir.

- You’d observe the transformation of local roads as Routes 21, 202, and 32A adapted to the new landscape.

- You’d marvel at the scale of earthworks needed to reshape the valley.

- You’d feel the tension as temporary dams held back the Swift River’s powerful flow.

Preserving Enfield’s Legacy

Since the waters of Quabbin Reservoir submerged Enfield in 1938, dedicated preservationists have worked tirelessly to maintain the town’s legacy through various initiatives.

Despite being underwater for over 80 years, Enfield’s spirit endures through the determined efforts of local preservationists and historians.

You’ll find historical documentation efforts led by local societies that maintain archives, photographs, and oral histories of the displaced community. Museums in neighboring towns showcase artifacts while commemorative markers near former town sites help you understand Enfield’s story.

The town’s memory lives on through annual remembrance events, digital mapping projects, and educational programs in watershed-area schools.

You’ll discover that state legislation supports these preservation efforts through PILOT programs and water usage taxes. Meanwhile, descendants of former residents keep family histories alive through reunions and genealogical records, ensuring Enfield’s heritage continues to resonate with future generations.

Modern Day Remnants and Memorial Sites

Today’s visitors to Enfield’s former location can discover tangible reminders of the lost town through carefully preserved sites and memorials.

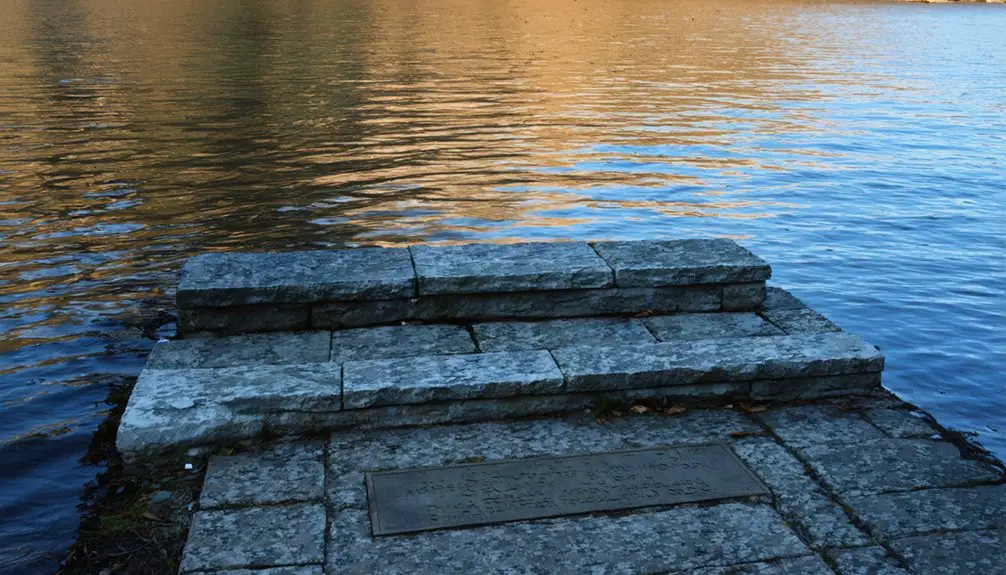

You’ll find remnant artifacts like cellar holes and granite steps along the reservoir’s edge, while memorial markers and interpretive plaques help tell Enfield’s story. From Enfield Lookout, you can survey the vast expanse of water that now covers this once-thriving community.

- Original stone foundations emerge during low water periods, offering fleeting glimpses into the past

- Historic railroad beds and truncated roads reveal the town’s former transportation network

- Eagles soar above the submerged valley where families once lived and worked

- Informational displays at nearby museums preserve the community’s memory

- Walking trails lead you to quiet spots where you can reflect on Enfield’s sacrifice

Frequently Asked Questions

Can Scuba Divers Explore the Submerged Remains of Enfield Today?

You can’t legally scuba dive or explore Quabbin Reservoir underwater, as it’s strictly prohibited to protect the drinking water supply. Authorities actively enforce these restrictions with fines and removal.

What Valuable Artifacts Were Left Behind During the Town’s Evacuation?

You won’t find many abandoned belongings since officials systematically removed and destroyed structures, relocated cemeteries, and cleared vegetation. Most items of historical significance were preserved in museums beforehand.

Are There Any Surviving Residents Who Lived in Enfield Still Alive?

While a million Enfield memories fade into history, you won’t find any confirmed living residents today – the last resettlement happened over 75 years ago, making resident stories increasingly precious historical records.

How Deep Is the Water Above Where Enfield’s Town Center Stood?

You’ll find about 150 feet of water above Enfield’s former town center in Quabbin Reservoir, as it sits in one of the deepest sections of the flooded Swift River Valley.

The history of Greenwich, Massachusetts, is marked by its early settlers who contributed to the region’s rich cultural fabric. Over time, the town transformed from a bustling agricultural hub to a quiet, scenic area that now attracts visitors seeking to explore its historical roots. The remnants of its past are still visible in the architecture and landmarks scattered throughout the landscape.

Did Any Buildings Survive Above Water Level After the Flooding?

You won’t find any original buildings standing above water level – all submerged structures were demolished or removed before flooding. Historical preservation efforts focused on documenting and relocating materials rather than preserving buildings intact.

References

- http://scua.library.umass.edu/enfield-mass/

- https://www.harvardmagazine.com/2023/08/quabbin-reservoir-lost-towns-elena-palladino

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quabbin_Reservoir

- https://quabbinhouse.com

- https://www.mass.gov/news/the-quabbin-reservoir-and-the-laws-that-shaped-it

- https://enfieldhistoricalsociety.org/old-town-hall/the-settling-of-enfield/

- https://enfieldhistoricalsociety.org/enfield-history/

- https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~nyterry/genealogy/towns/enfield/enfieldhis.html

- https://connecticuthistory.org/connecticuts-oldest-english-settlement/

- http://www.onenewengland.com/article.php?id=218