You’ll find Hide Town‘s remnants along Sweetwater Creek in the Texas Panhandle, where it emerged in 1874 as a buffalo hunters’ camp. Charles Rath’s trading post anchored this frontier settlement, which grew to 150 residents by 1875. Buffalo hides sold for up to $15, attracting hunters, soldiers, and entrepreneurs until the 1890s. Though the town declined after Fort Elliott’s closure and a devastating 1898 tornado, its wild frontier tales still echo across the prairie.

Key Takeaways

- Hide Town was established in 1874 as a buffalo hide trading post in Texas, growing to 150 residents by 1875.

- The settlement featured buffalo-hide shelters and thrived on hide trade, with prices ranging from $5 to $15 per hide.

- Fort Elliott’s closure in 1890 and the disappearance of buffalo populations led to the town’s economic decline.

- A devastating tornado in 1898 marked the final blow to Hide Town, causing residents to abandon the settlement.

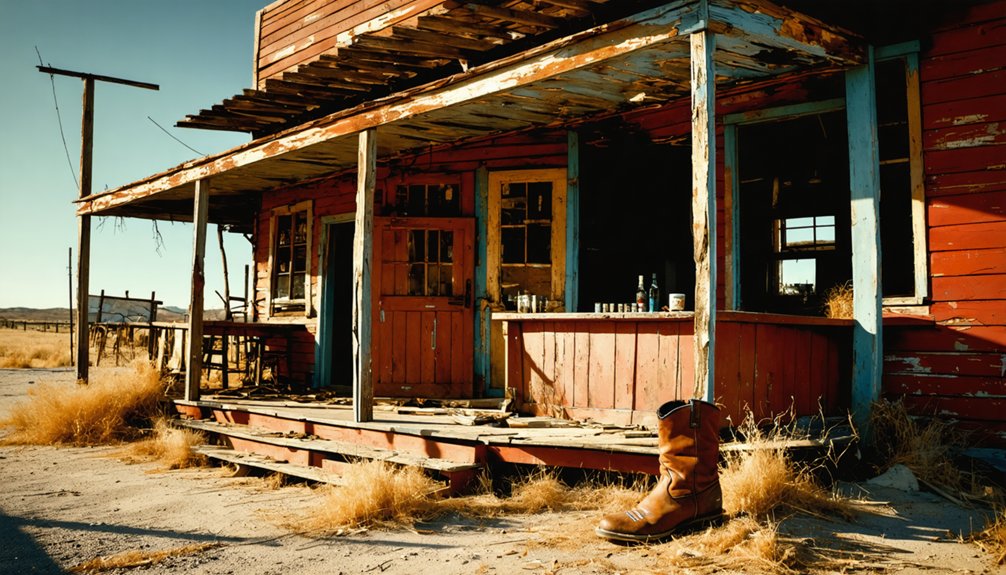

- Today, Hide Town exists as a ghost town with few remaining structures, serving as a historical reminder of Texas’s buffalo trade era.

The Birth of a Buffalo Hunters’ Camp

While the Texas Panhandle‘s vast grasslands attracted countless buffalo hunters in the 1870s, it was the establishment of Hide Town in 1874 that created an essential hub for the region’s burgeoning hide trade.

You’ll find that this camp, originally known as Hidetown, grew up around Charles Rath and Bob Wright’s supply store on Sweetwater Creek, where buffalo hunting operations found their base of operations. Teams of skilled hunters used Sharps rifles to harvest the abundant bison in the surrounding plains.

By the following summer, the settlement had grown to 150 residents and served as a vital trading post for nearby Fort Elliott.

Life Along Sweetwater Creek

The bustling life along Sweetwater Creek emerged from Hide Town’s early success as a buffalo trading post.

You’d find a vibrant mix of cultural exchanges as buffalo hunters, soldiers, and entrepreneurs crossed paths at Charles Rath’s trading post or Henry Fleming’s Lady Gay saloon. The community dynamics centered around Fort Elliott’s military presence, where Buffalo Soldiers helped maintain order and contributed to the local economy. The Ring Town Saloon specifically catered to the African American Buffalo Soldiers.

You could spot wagon masters like William Dixon leading bull trains loaded with buffalo hides, while colorful characters such as Bat Masterson and Kate Elder frequented the town’s establishments. The town experienced tragedy when a violent dance hall shootout left Mollie Brennan and Sergeant King dead in 1876.

Chinese laundries operated alongside boarding houses and restaurants, creating a surprisingly diverse frontier atmosphere.

Despite its initial lawlessness, the town’s commerce thrived as traders moved over 150,000 buffalo hides during peak seasons.

From Hide Shelters to Frontier Town

You’ll find the initial core of Hidetown in the buffalo-hide shelters constructed by hunters who established the settlement along Sweetwater Creek in 1874.

The rudimentary dwellings quickly gave way to more permanent structures as the community expanded to serve Fort Elliott’s soldiers and the steady stream of traders moving along the Jones and Plummer Trail. Much like Plemons Crossing, the location proved ideal for travelers seeking safe passage through the region.

The town’s early development centered around a supply store established by pioneers Charles Rath and Bob Wright.

What started as basic hide shelters evolved into a proper frontier town complete with rock houses, trading posts, and essential services that would help establish Hidetown’s role as the “mother city” of the Texas Panhandle.

Buffalo Hide Building Origins

Primitive buffalo hide shelters marked the humble beginnings of Hide Town’s transformation into a frontier settlement. You’d have found these makeshift structures dotting the Texas plains during the late 1800s, where buffalo hunters established temporary camps that would eventually grow into bustling frontier communities.

The ingenuity of buffalo hide construction reflected the resourcefulness of frontier life. You’d see wooden frames or simple posts draped with sturdy buffalo hides, creating walls and roofs that protected inhabitants from harsh weather. The hunters sold their buffalo hides for between $5 and $15 each, fueling the town’s early economy.

These shelters, clustered together in rough-hewn camps, drew more hunters and traders to what locals called “hide towns.” The practical design borrowed from Indigenous peoples’ traditional knowledge, making the most of every buffalo resource.

Such camps, like “Robber’s Roost” near Snyder, embodied the raw spirit of Texas frontier life. The area was established when Pete Snyder set up his trading post along Deep Creek, attracting both lawful settlers and questionable characters to the region.

Early Settlement Growing Pains

While buffalo hide shelters marked Hide Town’s earliest days, significant changes swept through the settlement after Charles Rath and Bob Wright established their permanent camp along Sweetwater Creek in 1874. The frontier post quickly attracted buffalo hunters, traders, and soldiers from nearby Fort Elliott, transforming the primitive camp into a bustling outpost of 150 residents by 1875.

Despite settlement challenges, including the rough frontier lifestyle and transient population, you’d have found a surprisingly diverse community taking shape. Chinese entrepreneurs opened a laundry, while saloons, restaurants, and dance halls catered to soldiers and hunters alike. The area became known as “the Flat” due to its distinct geographic features. The settlement’s first store was built by Charlie C. Rath in 1875.

The hide trade brought prosperity, with Rath, Wright, and Reynolds purchasing over 150,000 buffalo hides. This economic foundation spurred the community’s resilience, leading to more permanent structures and establishing Hide Town as an essential frontier hub.

Rustic Shelter to Commerce

From its namesake buffalo hide shelters in 1874, Hide Town rapidly evolved into a structured frontier settlement.

You’d have found the earliest residents making do with transient housing crafted from buffalo hides, perfectly suited to the raw frontier conditions near Sweetwater Creek. As buffalo hunting declined, you’ll notice how the community transformed when Henry Fleming built the first rock house, marking a shift toward more permanent rustic architecture.

You can trace the town’s growth through its strategic relocation closer to Fort Elliott in 1878, where brick and frame buildings replaced temporary shelters.

The settlement’s development accelerated as traders, hunters, and soldiers created a bustling commerce hub. Notable figures like Bat Masterson and Poker Alice helped establish Hide Town as an essential stop along the Jones and Plummer Trail.

The Military Influence of Fort Elliott

After the Second Battle of Adobe Walls in 1875, Fort Elliott emerged as a pivotal military outpost that transformed the Texas Panhandle frontier.

You’ll find its strategic location on a plateau overlooking Sweetwater Creek served as the perfect vantage point for military strategy and maintaining troop morale during challenging frontier operations.

The fort’s garrison included 200 soldiers from the 6th US Cavalry, 5th Infantry, and the renowned Buffalo Soldiers, who patrolled the borders and protected crucial cattle drives.

You can trace their impact through the fort’s expansion, which grew to include officers’ quarters, barracks, and a 12-bed hospital.

The military presence didn’t just secure the region – it sparked the growth of Mobeetie, the Panhandle’s first established town, making Fort Elliott a cornerstone of Texas frontier development.

Wild West Characters and Lawlessness

During its peak in the 1870s, Hide Town earned its infamous nickname “Robber’s Roost” by attracting a colorful cast of Wild West figures who blurred the lines between lawman and outlaw.

You’d find legendary characters like Garrett, Poker Alice, and Bat Masterson operating within this morally ambiguous frontier, where outlaw culture thrived alongside attempts at law enforcement.

The town’s roots as a buffalo hunters’ camp drew a rough crowd of transients, gamblers, and those seeking quick fortunes.

Even Henry Fleming, Wheeler County’s first sheriff, exemplified the lawman duality of the era, building his rock house near the untamed buffalo camps.

With minimal formal authority, the townspeople relied on vigilante justice and improvised courts to maintain order, creating a volatile mix of frontier justice and lawlessness that defined Hide Town’s character.

Trading Post Economics

The economic heartbeat of Hide Town centered on William Henry “Pete” Snyder’s trading post, established in 1878 along Deep Creek’s strategic banks.

The trading post dynamics revolved around the flourishing buffalo hide trade, with hunters clustering their hide dwellings nearby, earning the settlement its early nickname.

You’d find the post buzzing with economic exchanges, as traders swapped essential goods, tools, and provisions with buffalo hunters and settlers.

As the trading post’s influence grew, Snyder seized the opportunity to transform Hide Town into a planned settlement, selling plots of land to enthusiastic newcomers.

The Decline and Legacy

You’ll find Hide Town’s decline followed a familiar pattern among Texas ghost towns, with its economic lifeline weakening after the 1890s as buffalo hunting ceased and cattle operations shifted elsewhere.

The town’s population dwindled steadily over decades rather than experiencing the sudden exodus common to mining settlements, with families gradually moving away as trading opportunities diminished.

While little remains of Hide Town’s physical structures today, its role in the Texas buffalo trade and frontier commerce continues to interest historians studying the state’s economic transformation during the late 19th century.

Slow Death After 1890s

Following Fort Elliott’s permanent abandonment in October 1890, Hide Town and neighboring Mobeetie entered a devastating period of decline that would ultimately seal their fate as ghost towns.

The region’s economic isolation intensified as buffalo populations vanished and failed attempts to secure railroad connections left these frontier communities stranded.

You’ll find that a social transformation swept through the area in the 1890s, with religious revivals attempting to reshape the once-lawless towns through church construction and saloon closures.

Yet these changes couldn’t prevent the towns’ downward spiral. The final blow came with the destructive tornado of 1898, which killed seven people and left many buildings in ruins.

Rather than rebuild, most remaining residents chose to abandon these struggling communities for opportunities elsewhere.

Enduring Historical Significance

Despite its eventual decline, Hide Town’s enduring legacy as a pivotal frontier settlement continues to resonate through Texas history. You’ll find its influence preserved in historical artifacts like buffalo-hide buildings and cultural memory passed down through generations of Texans.

The town’s evolution from a rugged buffalo hunters’ camp to Mobeetie exemplifies the raw spirit of frontier adaptation and survival.

As one of the Texas Panhandle’s earliest European-American settlements, the site offers you a tangible connection to legendary frontier figures like Bat Masterson and Pat Garrett.

Its role in regional commerce, law enforcement, and the shift from Native American territory to settled community makes it an invaluable window into the complex social dynamics of the American West’s expansion.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Happened to Henry Fleming’s Rock House After the Town Declined?

You’ll find that Henry Fleming’s Rock House remained standing through the settlement era, with its stone walls enduring as a historical marker and symbol of frontier permanence, even after the town’s decline.

Were There Any Notable Native American Conflicts Specifically in Hidetown?

Like shadows on the prairie, no specific Native American Wars were documented in Hide Town itself, though the area felt ripples of broader Tribal Relations conflicts in the Texas Panhandle region.

What Types of Businesses Operated in the Town Besides Trading Posts?

You’d find bustling saloon operations, busy livery stables, active blacksmith services, well-stocked drugstores, and hotels welcoming travelers. Barbershops kept folks groomed while boarding houses provided longer-term lodging.

How Did Residents Get Their Drinking Water in Hidetown?

You’d find your drinking water from Sweetwater Creek, the main water source for Hidetown’s residents. With no community wells documented, you’d rely on collecting surface water directly from the creek.

Did Any Original Buildings From Hidetown Survive to the Present Day?

Time has wiped the slate clean in Hidetown – you won’t find any surviving structures there today. Despite growing interest in historical preservation across Texas, no original buildings managed to weather the years.

References

- https://www.texasalmanac.com/places/hidetown-0

- https://mix941kmxj.com/the-strange-sad-story-of-a-texas-ghost-town-youll-never-visit/

- https://www.legendsofamerica.com/tx-mobeetie/

- https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/mobeetie-tx

- https://texashighways.com/travel-news/four-texas-ghost-towns/

- https://www.southernthing.com/ruins-in-texas-2640914879.html

- https://petticoatsandpistols.com/2017/08/15/rough-wooly-hidetown/

- https://www.ghosttowns.com/states/tx/mobeetie.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Texas

- https://buffalogaptx.com/the-buffalo-hunters-audio-tour/