You’ll find Princeton, Texas’s ghost town remnants near the Sabine River, where it once thrived as Possum Bluff in 1839. The settlement served as a crucial ferry crossing and commerce hub, later hosting a WWII POW camp and migrant worker housing. Despite its promising start, the town declined when major railways bypassed it, and natural disasters struck. Today, this Newton County ghost town shouldn’t be confused with modern Princeton in Collin County – its story reveals fascinating historical twists.

Key Takeaways

- Originally established in 1839 as Possum Bluff along Princeton Bluff near the Sabine River, serving as an early commerce hub.

- Economic decline accelerated due to major railroad lines bypassing the town and inadequate transportation infrastructure.

- The town suffered a devastating tornado in 1948, destroying the Methodist Church and hampering post-war recovery efforts.

- By the early 1900s, the original Princeton settlement faced near-complete abandonment as families sought opportunities elsewhere.

- Located in Newton County near the Sabine River, distinct from the modern Princeton in Collin County near Dallas.

Origins on Princeton Bluff

When settlers first established Princeton in 1839, they strategically chose Princeton Bluff’s elevated terrain along the Sabine River, about 30 miles northeast of present-day Beaumont.

Also known as Possum Bluff, this location offered critical advantages for early commerce and river transportation in southeastern Texas. The area’s atmospheric conditions frequently created ghostly fog formations at night, reminiscent of the eerie mists that would later be reported at Princeton University.

You’ll find the settlement’s origins deeply tied to its river-based functionality. The bluff’s natural elevation provided an ideal position for a ferry crossing and boat landing, making it a practical stop for travelers and merchants moving along the Sabine River.

While the town’s founders had visions of creating a thriving river port, Princeton’s development would remain modest, focused primarily on serving as a transit point for river commerce rather than expanding into a major settlement. Unlike its namesake College of New Jersey, which was established in 1746 and later became Princeton University, the Texas town would never achieve the same level of prominence.

Life Along the Sabine River

Along the winding Sabine River, life flourished amid a rich ecosystem of longleaf pine, oak, and cypress forests that supported both native peoples and early settlers. The natural beauty was enhanced by ancient Bald Cypress trees that towered over the landscape, some surviving for more than 800 years.

Ancient forests of pine, oak and cypress lined the meandering Sabine, nurturing generations of inhabitants along its fertile banks.

You’ll find that the Caddo Indians thrived here for over 500 years, establishing river settlements that became part of a vast network of Native American communities. The river ecosystems provided abundant resources, pushing nearly 7 million acre-feet of water annually into the Gulf of Mexico. The first steamboat named Sabine ventured up the river in 1843, marking a new era of transportation.

When European and American settlers arrived in the early 19th century, they transformed the landscape with logging operations and sawmills.

Historical settlements like Ebarb and Pine Flat developed strong connections to the river until the Toledo Bend Dam project displaced them. The fertile soils and plentiful water sustained agriculture, while later oil exploration brought new economic opportunities to the region.

Failed Growth and Development

Despite its early agricultural promise in the late 1870s, Princeton struggled to achieve sustainable growth due to several critical limitations.

Failed infrastructure and economic setbacks plagued the town’s development, from inadequate transportation routes to devastating natural disasters. The construction of the Missouri Kansas Railroad in 1881 provided only temporary economic relief. Today’s 121 Corridor has completely transformed the area’s economic potential.

Failed growth was particularly hindered by controversial land grabs and legal battles that shook investor confidence in the 2010s.

- You can still see the scars of the 1948 tornado that destroyed the Methodist Church and crushed the town’s post-war momentum.

- The town’s isolation from major railways left farmers struggling to get their crops to market.

- Princeton’s desperate “strip annexation” attempts revealed a town fighting for survival.

- The seasonal nature of agricultural work never created the stable population needed for true prosperity.

The Migratory Worker Settlement

As Princeton faced mounting agricultural labor shortages in 1940, local farmers established an essential migratory worker settlement on the western edge of town, where today’s Community Park stands. The camp addressed vital labor challenges by housing 300-400 seasonal workers in 76 California redwood cabins during peak harvest periods. Toward the end of WWII, the site became one of 511 POW camps across America.

You’ll find the migrant experiences were centered around basic but structured living conditions. Each cabin featured two beds, an oil cook stove with oven, oil heater, and chairs. A 30,000-gallon water tower served the community’s needs.

In 1945, the site briefly became a German POW camp before returning to its original purpose. During their stay, prisoners earned two dollars a day for agricultural work under Geneva Convention rules. While the original structures are gone, the settlement’s legacy lives on through a historical marker, reminding visitors of Princeton’s agricultural heritage and its significant role in sustaining local farming during times of change.

World War II POW Camp Operations

You’ll find that the German POW camp in Princeton operated efficiently from February 1945 to January 1946, housing up to 25 prisoners who lived in well-equipped redwood cabins with modern amenities like oil stoves and heaters.

The POWs earned two dollars per day working on local farms and construction projects, helping to offset the wartime labor shortage while building parts of downtown Princeton’s stonework. The camp was one of 70 POW facilities across Texas during World War II. Local farmers regularly employed the prisoners for essential agricultural work during the eight-month period.

Their presence left a lasting impact on the community through their contributions to local infrastructure, including a memorial park commemorating WWII servicemen.

POW Camp Daily Life

Life for German POWs at the Princeton camp followed a structured routine centered around farm labor and civic projects. You’ll find their daily activities were governed by Geneva Convention rules, with prisoners earning $2 per day for their work.

They’d be transported by truck to local fields and worksites, much like the migrant workers who’d occupied the camp before them.

- You can imagine their voices carrying across town as they sang German songs during their initial march to camp

- Their handiwork still stands in Princeton’s community park and war memorial

- They lived in relative comfort with access to showers, washing machines, and a church

- They maintained an orderly existence with no documented escape attempts

The camp’s emphasis on productive work and decent living conditions helped keep the prisoners content throughout their stay.

Labor Impact and Changes

During World War II, Princeton’s farms faced a severe labor crisis when military enlistment depleted the local workforce. You’d find the town struggling with labor shortages that threatened agricultural sustainability until German POWs arrived in February 1945.

The POW workforce proved invaluable, helping you maintain essential farm operations when migrant workers weren’t available. They’d work the fields daily, transported by trucks from their camp, and even contributed to civic projects like building parks and war memorials.

You’d see them earning about two dollars per day under Geneva Convention requirements. Their presence helped prevent costly agricultural imports and kept local farms running until January 1946.

Despite initial community concerns, the POWs’ cooperative attitude and strict camp security measures guaranteed smooth operations throughout their stay.

Post-War Transformation

While Princeton’s wartime role as a German POW camp ended in late 1945, the town’s transformation in the post-war era was marked by a return to its agricultural roots.

Princeton transitioned from wartime prison camp to peaceful farming community in 1945, embracing its enduring agricultural heritage once again.

You’ll find that the post-war economy shifted back to supporting seasonal labor, with the former POW camp once again housing migrant workers who were essential to the cotton and onion harvests.

- You can still picture the 76 California redwood cabins that housed up to 400 workers during peak seasons.

- You’d have seen the massive 30,000-gallon water tank standing as a symbol to the camp’s infrastructure.

- You might’ve witnessed the daily rhythm of agricultural life resuming after the war’s disruption.

- You’d recognize how the camp’s transformation reflected the broader pattern of rural Texas communities readjusting to peacetime.

Decline and Disappearance

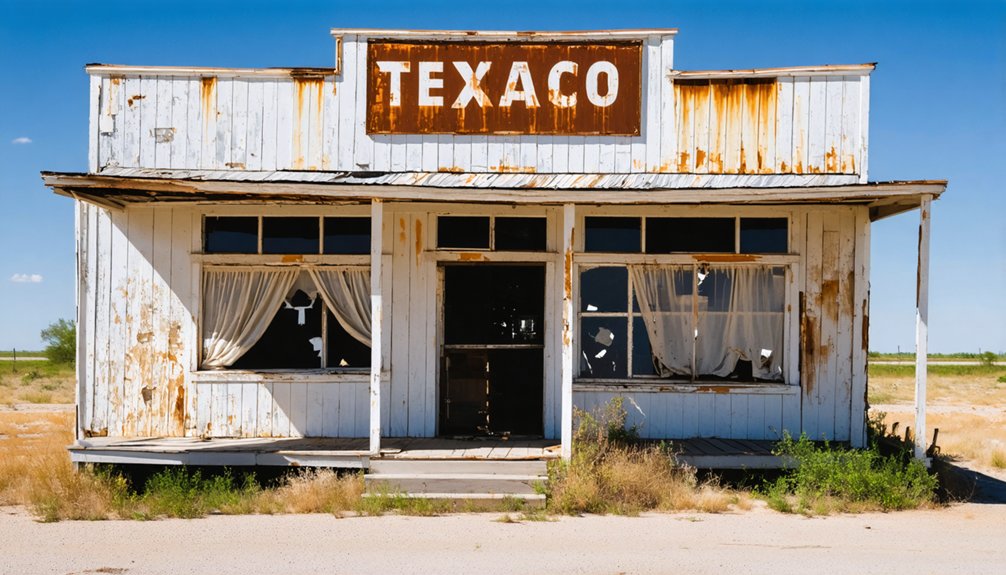

The gradual decline of Princeton began as economic limitations and regional competition took their toll on the once-bustling agricultural community.

You’ll find that economic stagnation set in when major railroad lines bypassed the town, while the growing settlement of Deweyville attracted businesses and residents away from Princeton’s struggling marketplace.

Population decline accelerated as families sought better opportunities elsewhere, leading to the closure of schools, stores, and community institutions.

Princeton’s unfavorable geographic location and limited natural resources couldn’t sustain its agricultural base, while poor transportation links isolated it from regional markets.

By the early 1900s, you’d have witnessed the town’s near-complete abandonment, with most structures falling into disrepair or being demolished.

Today, Princeton exists primarily in historical records, with few physical remnants marking its former existence.

Legacy in Newton County

Remnants of Princeton’s brief but significant legacy endure in Newton County’s historical narrative, particularly through its role as an early river transportation hub.

While you won’t find historical markers or active preservation efforts at Princeton today, its story illuminates the county’s pioneering spirit and early settlement patterns.

The town’s cultural visibility has faded, yet its impact on regional transportation networks can’t be erased from local heritage dialogues.

- You can trace the town’s influence in early ferry crossing routes that shaped Newton County’s development.

- You’ll find Princeton’s story woven into the fabric of Sabine River commerce chronicles.

- You’re walking on ground that once served as an essential link between Texas settlements.

- You’re experiencing a piece of history that represents the freedom of river-based frontier life.

Geographic Distinctions From Modern Princeton

You’ll find the ghost town of Princeton in Newton County near the Sabine River, while modern Princeton sits in Collin County – two completely separate locations hundreds of miles apart.

The ghost town emerged as a rural riverside settlement in deep Southeast Texas, contrasting sharply with modern Princeton’s development as a railroad town along the Missouri, Kansas and Texas line in the fertile Blackland Prairie.

These distinct geographic settings shaped vastly different population patterns, with the Newton County site remaining sparsely populated before its abandonment, while the Collin County Princeton grew into a thriving agricultural and commercial center.

Location and County Differences

While sharing the same name, Princeton ghost town and modern Princeton occupy vastly different regions of Texas, separated by hundreds of miles and distinct geographical features.

You’ll find the ghost town perched on Princeton Bluff along the Sabine River in Newton County, where it once served as a historical ferry and river commerce hub. In contrast, modern Princeton sits in Collin County’s Blackland Prairie region, about seven miles east of McKinney.

- The ghost town’s riverside location made it a crucial stop for early Texas river travelers.

- Newton County’s Princeton represents untamed frontier spirit along the Louisiana border.

- Modern Princeton thrives in the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex’s expanding reach.

- Each Princeton falls under different county jurisdictions, shaping their distinct destinies.

River vs. Railroad Towns

As river and railroad towns emerged across Texas, their distinct geographic features shaped vastly different destinies for each settlement type.

River commerce defined early settlements, with towns clustering around waterways for trade, agriculture, and transportation.

These communities faced constant flooding challenges while adapting to seasonal changes in water levels.

Population Development Patterns

Despite its original humble beginnings as Wilson Switch, Princeton’s population development has followed a remarkable trajectory that sets it apart from typical ghost town patterns.

You’ll find that Princeton’s population trends showcase a thriving community that’s grown from a small farming settlement to a bustling city of 37,019 residents in 2024. The community growth has been particularly dramatic since 2020, when the population was just 17,027.

- Your freedom to explore Princeton’s historic charm while enjoying modern amenities reflects the town’s successful evolution.

- You’ll witness the transformation of the former migratory camp into a vibrant community park.

- You’re part of a dynamic community that’s preserved its agricultural heritage while embracing progress.

- You’ll experience the benefits of strategic location near major highways that fuels continued growth.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are There Any Remaining Structures or Ruins Visible at Princeton Today?

You won’t find any abandoned remaining buildings or structural remnants in Princeton today – the city’s rapid growth has replaced older structures with new development, leaving no visible ruins.

What Happened to the German POWS After Leaving the Princeton Camp?

After their release in January 1946, you’ll find most POWs were repatriated to Germany, facing post war integration challenges. Some maintained positive memories of their time, while others struggled with repatriation challenges.

Did Any Notable Historical Figures Ever Visit or Live in Princeton?

You won’t find any famous visitors or nationally recognized historical figures in Princeton’s past. Besides Prince Dowlin, who gave the town its name, and German POWs, local farmers shaped its historical significance.

What Native American Tribes Originally Inhabited the Princeton Area?

You’ll find rich cultural heritage in the Caddo, who dominated the area, along with Cherokee, Delaware, Kickapoo, and Tonkawa tribes. Their tribal history shows they shared this land before European settlement.

Were There Any Documented Criminal Activities or Conflicts in Princeton’s History?

Like pages torn from history’s book, Princeton’s most notable criminal conflicts include the tragic 1988 Angela Stevens murder. Beyond that case, historical records show relatively few documented serious crimes in your area.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Princeton

- https://paw.princeton.edu/article/ghosts-princeton

- https://www.princetontx.gov/168/History-of-Princeton

- https://kids.kiddle.co/Princeton

- https://www.texasescapes.com/CentralTexasTownsNorth/Princeton-Texas.htm

- https://princetonlowrycrossing.com/princeton-history/

- https://www.dailyprincetonian.com/article/2023/11/princeton-features-cemetery-ghost-tour

- https://www.princetonmagazine.com/top-ten-haunted-places-in-princeton/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Texas

- https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/town-bluff-tx