You’ll discover the remains of an early Quaker settlement in eastern Indiana that thrived from 1809 through the late 1800s. The community, anchored by the Whitewater Monthly Meeting, built homes, schools, and safe houses for the Underground Railroad. While discrimination and economic hardships eventually led to its decline, you can still find weathered foundations, cemetery stones, and artifacts like glass fragments that tell the story of these pioneering religious folk.

Key Takeaways

- Archaeological excavations at Dead Man’s Curve revealed artifacts from daily Quaker life, including glass fragments, whiteware, and stoneware items.

- Foundation remains and unmarked cemetery stones provide physical evidence of abandoned Quaker settlements in Indiana’s frontier regions.

- Economic pressures, lack of infrastructure, and market downturns forced many Quaker families to abandon their settlements seeking better opportunities.

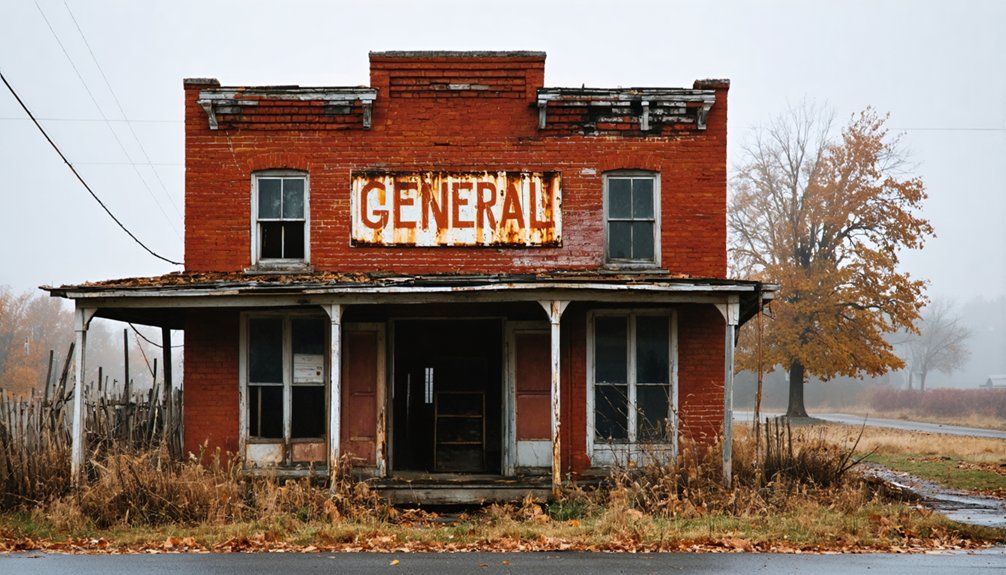

- Most original Quaker settlements became ghost towns as populations declined and families migrated away from their established communities.

- Modern preservation efforts focus on protecting remaining cemetery markers and historical sites of former Quaker settlements throughout Indiana.

The Origins of a Peaceful Settlement

When the War of 1812 finally ended, Quaker families from the Carolinas and Tennessee began pouring into Indiana’s untamed wilderness, seeking both religious freedom and fresh opportunities.

Driven by faith and dreams of a new life, Quaker pioneers left their southern homes behind for Indiana’s wild frontier.

You’ll find their settlement patterns closely followed their Quaker beliefs, with families establishing remote cabins far from civilization but eventually linking up through a network of monthly meetings.

Indiana’s status as a non-slaveholding state made it particularly attractive to these Quaker settlers seeking to distance themselves from slavery.

It all started with the Whitewater Monthly Meeting in 1809, which served as the mother meeting for Indiana’s growing Quaker population.

From there, new settlements branched out like spokes on a wheel – Blue River in Washington County, Lick Creek in Orange County, and New Garden in Wayne County.

Each settlement became a beacon of freedom, drawing more families to the frontier.

The Western Yearly Meeting organized in 1858 became a significant gathering point for the Quaker communities.

Daily Life in Early Quaker Communities

Deep in Indiana’s frontier settlements, you’d find Quaker families building their lives around a rich tapestry of communal activities and shared labor. Your daily routines would revolve around working the land, tending to crops, and caring for livestock alongside your neighbors.

You’d join community gatherings for barn raisings, harvest time, and First-day worship meetings, where spiritual and practical matters intertwined.

In these close-knit communities, you’d see women and children tending gardens and handling household duties while men tackled heavy fieldwork and carpentry. The early schooling of children took place in settler homes like Peter Hoover’s cabin. Democratic decision-making ensured every member of the community had a voice in important matters.

Local mills, powered by nearby rivers, would grind your grain, and craftsmen would help build your home from native timber.

Through it all, you’d experience the strength of Quaker values – equality, simplicity, and peaceful cooperation – shaping every aspect of frontier life.

Underground Railroad Activities and Abolitionist Legacy

Throughout the mid-1800s, Indiana’s Quaker communities became essential lifelines in the Underground Railroad network, with settlements stretching from Richmond to Blue River serving as key stations for freedom seekers.

Led by notable figures like Levi Coffin, who you might’ve heard called the “President of the Underground Railroad,” these Quaker networks developed sophisticated abolitionist strategies to guide escapees northward.

You’d find safe houses dotting the eastern route along the Indiana-Ohio border, while others followed the Wabash River valley westward.

The most intricate operations happened in places like Wayne and Randolph Counties, where Quaker families worked together, often risking arrest to shelter fugitives.

They’d coordinate with folks like Dr. Luther Jewett in Lafayette and Joshua Trueblood in Washington County to guarantee safe passage to Michigan or Chicago.

Secret rooms and hidden areas in Quaker homes served as carefully concealed hideouts for those seeking freedom.

After the Federal Fugitive Law of 1850, these brave abolitionists faced even greater dangers as they continued their work helping escaped slaves reach freedom.

Economic Challenges and Population Decline

While these Quaker settlements stood as beacons of hope for freedom seekers, they faced mounting economic pressures that would ultimately test their resilience.

Despite offering sanctuary and promise, Quaker havens for freedom seekers struggled against economic hardships that threatened their very existence.

You’ll find that economic integration proved challenging for African American residents, who encountered discrimination despite strong Quaker support systems. The lack of adequate infrastructure and limited access to resources made farming difficult, and when market conditions turned sour, many families couldn’t keep up with their taxes. Many families faced additional strain as local newspapers criticized their pacifist stance during wartime.

As opportunities emerged elsewhere, you’d see shifting migration patterns take hold. Some folks headed to more promising regions, including Canada, while others moved to urban areas.

The combined effects of these challenges – from disease outbreaks to agricultural struggles – gradually emptied these settlements, leaving only old cemeteries and building foundations as silent witnesses to their once-thriving communities. By the mid-1800s, Lick Creek had grown to approximately 200 families before its population began declining sharply during the Civil War era.

Archaeological Discoveries and Preserved Artifacts

You’ll discover fascinating domestic remnants at the Dead Man’s Curve site, where archaeologists found everyday items like broken scissors, slate pencils, and marbles that paint a picture of daily life in historic Quaker, Indiana.

The site’s recent significance was further elevated when a 4,000-year-old skull was discovered along the nearby Whitewater River, adding a deeper historical layer to the region’s archaeological importance. University researchers conducted DNA extraction analysis to reveal insights about ancient migration patterns and biological traits of early inhabitants.

A key discovery was the burned house structure with wall-trench construction, where the northern and eastern walls collapsed onto a highly compacted floor during what appears to be a destructive fire.

The site’s social stratification becomes clear through the artifact counts – poorer households typically yielded around 20 items while more affluent sites contained over 130 artifacts, including decorative transfer-printed wares.

Unearthed Tools and Objects

Archaeological excavations at Quaker settlement sites have revealed a treasure trove of tools and objects that paint a vivid picture of daily life in early Indiana.

You’ll find humble yet telling artifacts from the early 1800s, including aqua glass fragments, plain whiteware, and practical stoneware pieces scattered across these sites. Unlike earlier Native American tool manufacturing areas that yielded elaborate burial artifacts and ceremonial items, Quaker settlements showcase a simpler material culture focused on utility and modest living.

When you explore these sites today, you’ll discover everyday items that tell stories of frontier life – from basic architectural remains like brick fragments to domestic tools used in food preparation.

These artifacts reflect the Quakers’ commitment to simplicity and self-sufficiency, showing how they carved out their existence in 19th-century Indiana.

Building Foundation Remains

Beyond the scattered tools and everyday objects, the building foundations at these Quaker settlement sites offer compelling physical evidence of frontier life.

You’ll find fascinating historical architecture in the wall trenches and post pits, similar to those discovered at Dead Man’s Curve. Foundation archeology reveals how these pioneers adapted their building techniques, shifting from Late Woodland to more advanced Mississippian construction styles.

Despite the challenges of plow damage and erosion, you can still trace the outline of where these freedom-loving settlers made their homes.

When you examine the burned house remains at Dead Man’s Curve, you’ll notice evidence of rebuilding efforts – a reflection of their resilience and determination to maintain their community.

These structural remains continue to tell the story of Indiana’s early Quaker settlements and their quest for liberty.

Cemetery Stone Documentation

The stark simplicity of Quaker cemetery stones tells a compelling story about early Indiana settlers’ religious values.

You’ll find that until the 1860s, most Quakers wouldn’t even mark their graves, believing tombstones showed vanity. When they did use markers, they’d opt for plain fieldstones or modest marble tablets with just names and dates.

Archaeological work at Indiana’s Quaker cemeteries has revealed various gravestone styles, from simple unmarked stones to later granite markers.

Today, you can spot the evolution of these burial customs in preserved sites like Denny Cemetery. While some graves were relocated in the late 1800s, many original burial spots remain, protected by modern preservation efforts.

Fencing and documentation projects help safeguard these humble markers that reflect the Quakers’ deep commitment to equality and simplicity.

Historical Significance in Modern Indiana

Despite its physical remnants fading into Indiana’s forested landscape, Lick Creek’s historical significance continues to shape modern discussions of racial integration and religious tolerance in the Hoosier State.

You’ll find this early 1800s settlement’s story woven into local historical narratives, showcasing how free African Americans and Quakers built a thriving integrated community when most of America remained strictly segregated.

The settlement’s community resilience in defying social norms of its time serves as a powerful teaching tool in Indiana’s schools today.

While the physical town has vanished into the Hoosier National Forest, its legacy endures as a symbol of what’s possible when people choose cooperation over division, making it a cherished piece of Indiana’s multicultural heritage.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were There Any Reported Paranormal Activities in Abandoned Quaker Settlements?

You won’t find documented ghost sightings in abandoned Quaker settlements. While Indiana has many haunted locations, there’s no verified paranormal evidence specifically tied to former Quaker communities or their ghost towns.

However, there are still numerous ghost town attractions in Packard that capture the interest of thrill-seekers and history buffs alike. These sites often feature intriguing tales of the past, drawing visitors to explore the remnants of a once-vibrant community. The eerie atmosphere and decaying structures provide a unique glimpse into a bygone era, making them popular destinations for urban explorers and photographers.

What Traditional Quaker Recipes and Foods Were Unique to Indiana Settlements?

You’ll find Indiana’s Quaker cuisine centered on Sugar Cream Pie, a signature dessert from traditional baking that emerged when eggs were scarce. Local dried fruits and hearty cornmeal dishes were also uniquely Hoosier-Quaker staples.

How Did Native American Tribes Interact With Quaker Communities?

Like a cosmic GPS recalibrating, you’d find Native Americans and Quakers navigated complex relationships. While Penn’s 1682 treaty promoted cultural exchange and mutual respect, later interactions shifted toward forced assimilation and boarding schools.

What Games and Recreational Activities Were Popular in Quaker Settlements?

You’d find Quaker games centered on community gatherings – from singing schools and barn raisings to quilting bees. Kids played tag and hopscotch, while adults enjoyed storytelling, card games, and seasonal festivities.

Did Any Famous Historical Figures Visit These Indiana Quaker Communities?

While you won’t find records of famous historical visitors like Frederick Douglass in these settlements, notable residents like the Coffin and Trueblood families shaped local politics through their anti-slavery activism and community leadership.

References

- https://www.heraldtimesonline.com/story/lifestyle/home-garden/2020/05/01/ghost-towns-in-ohio-and-indiana/43807535/

- https://www.indianaconnection.org/gone-home-revival-lick-creek/

- http://ingenweb.org/intippecanoe/ghosttowns.htm

- https://indianahistory.org/wp-content/uploads/a9b3c346e4e669f4c182353d9dd6f35f.pdf

- https://www.blueriverfriends.org/index.php/salem-indiana-quaker-settlement/blue-river-quakers-and-slavery

- https://lincolnquakers.com/2019/09/27/indiana-view-of-quakers-during-the-civil-war/

- https://theclio.com/tour/2678

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Indiana

- https://theclio.com/entry/181895

- https://www.townofplainfield.com/1311/Town-History