Silverton isn’t technically a ghost town but a living historic mining community in Colorado’s San Juan Mountains. Founded after the 1873 Brunot Treaty displaced the Utes, it boomed when the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad arrived in 1882, then struggled following the 1893 Silver Crash. Today, this preserved mountain town serves as your gateway to authentic abandoned mining settlements nearby, including Animas Forks at 11,000 feet. The area’s remarkable preservation tells a deeper story of boom, bust, and reinvention.

Key Takeaways

- Silverton itself isn’t a ghost town but serves as a gateway to numerous abandoned mining communities in the San Juan Mountains.

- Animas Forks, once home to 450 residents at 11,000+ feet elevation, is a well-preserved ghost town accessible by 4×4 vehicles.

- The 1893 Silver Crash caused many mining communities to be abandoned as families left due to economic hardship.

- The San Juan County Historical Society has secured over $12 million for preserving historic structures throughout the region.

- Heritage tourism now sustains Silverton’s economy, with thousands visiting annually to experience the area’s mining history.

The Birth of Silverton: From Ute Lands to Mining Frontier

Long before Silverton became a mining boomtown, the San Juan Mountains were home to the Ute people, whose ancestral connection to this rugged landscape stretched back generations.

You’d find them moving with the seasons—hunting and gathering in summer mountain sanctuaries while wintering at lower elevations.

The Utes fiercely defended their homeland against Spanish and American incursions until the devastating Brunot Treaty of 1873 forced them to cede over four million acres.

The land fell to signatures on paper, a mountain homeland traded for empty promises and forgotten words.

This pivotal moment in Ute history transformed the region overnight.

After gold and silver discoveries along the Animas River in what miners called “Baker’s Park,” prospectors flooded in.

By year’s end, nearly 4,000 mining claims dotted the landscape.

Silverton emerged from this rush, establishing a mining legacy while erasing centuries of Indigenous presence.

The introduction of horses from Spain dramatically increased the Utes’ mobility and hunting capabilities across their territory.

The first permanent structure, a log cabin, was built by Francis Marion Snowden in 1874, marking Silverton’s official organization as a settlement.

Railway Revolution: How the Denver & Rio Grande Changed Everything

When the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad reached Silverton in 1882, you’d have witnessed an unprecedented transformation of this remote mining settlement into a booming economic center.

The narrow gauge line revolutionized ore transport, allowing hundreds of thousands of tons of precious metals to move efficiently from the San Juan Mountains to distant markets, generating over $300 million throughout its operational history.

Beyond freight, the passenger service connected Silverton’s once-isolated residents to the outside world, bringing essential supplies, new settlers, and eventually tourists who’d help sustain the town when mining declined. The railroad was constructed primarily by Chinese and Irish immigrants who were paid just $2.25 per day for their difficult and dangerous labor. This railway network was later expanded by Otto Mears, who built additional railroads to connect more isolated mining communities to the Denver & Rio Grande.

Railroad Arrival Effects

The arrival of the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad in 1882 transformed Silverton from an isolated mining camp into a thriving economic powerhouse almost overnight.

The 45-mile narrow gauge line, completed in just nine months by an immigrant workforce comprised mainly of Chinese and Irish railroad labor earning $2.25 daily, connected this remote mountain settlement to the outside world.

You’d have witnessed an explosion of prosperity as the tracks enabled the transport of over $300 million in precious metals throughout the region’s history.

The railroad’s engineering marvels—navigating 7% grades and 30-degree curves—opened previously inaccessible mining operations at higher elevations.

As Otto Mears expanded the network with three additional narrow gauge lines, Silverton became a four-railroad hub, cementing Colorado’s position as a leading precious metals producer in the nation.

The innovative narrow gauge tracks allowed trains to better navigate the challenging mountain terrain, making transportation through the rugged San Juan Mountains possible.

The railroad was initially promoted as a scenic route, though its primary purpose was to haul valuable mine ores from the San Juan Mountains to processing facilities.

Ore Transport Revolution

Prior to the Denver & Rio Grande‘s arrival in 1882, mining operations throughout Silverton’s rugged terrain struggled with the nearly impossible task of transporting ore via mule trains and wagons on treacherous mountain paths.

The narrow gauge railroad revolutionized mining logistics overnight. Built for just over $900,000 with steel rails spaced three feet apart, the line transformed how you’d get ore to market. What once took days now took hours.

The economic transformation was immediate – over $300 million in precious metals flowed through this crucial artery, positioning Colorado as a leading national producer. The railroad slashed transportation costs and extended mine lifespans throughout the region.

With Durango serving as the hub, this engineering marvel connected Silverton to a vast network that reshaped the isolated mining camp into a thriving economic center. The construction of this remarkable railroad took only 11 months to complete, showcasing the engineering prowess and determination of the era.

Passenger Service Impact

Beyond revolutionizing ore transportation, the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad dramatically reshaped human connections throughout the San Juan Mountains with its passenger service.

You’d have experienced a remarkable evolution in the passenger experience from 1882 onward. What began as essential transportation transformed into one of Colorado’s premier tourist attractions, preserving the region’s heritage when most narrow-gauge lines disappeared. The railroad carried 25,000 passengers in the summer of 1957, generating substantial revenue and boosting local economies. The railroad has maintained continuous operation since 1882, using both historic steam and diesel locomotives to transport visitors.

– The introduction of Pullman cars brought unexpected luxury to this remote mining region.

- Mixed train operations adapted to seasonal demands, keeping communities connected.

- “The Silverton” summer service, launched in 1947, capitalized on post-war tourism.

- The Silver Vista Car’s glass-topped design showcased the breathtaking mountain vistas.

- Original wooden structures including the jail and William Duncan Home

- Evidence of tunnels dug through 25-foot snowdrifts during the legendary 1884 blizzard

- Remnants of daily life where mining dangers claimed many lives

- Alpine beauty that both enchanted and threatened settlers with thunderstorms and avalanches

- Tight-knit community bonds built over generations

- Local stores stocked for prolonged periods without outside access

- Community traditions that maintain morale through the snowbound months

- Robust emergency preparedness systems that neighbors rely on

- Families departed south each fall when temperatures plummeted

- Only the hardiest individuals remained behind

- Social networks in Silverton provided essential support systems

- Miners planned their work schedules around these seasonal shifts

- The William Duncan House (1879) with its practical small windows designed for brutal mountain winters

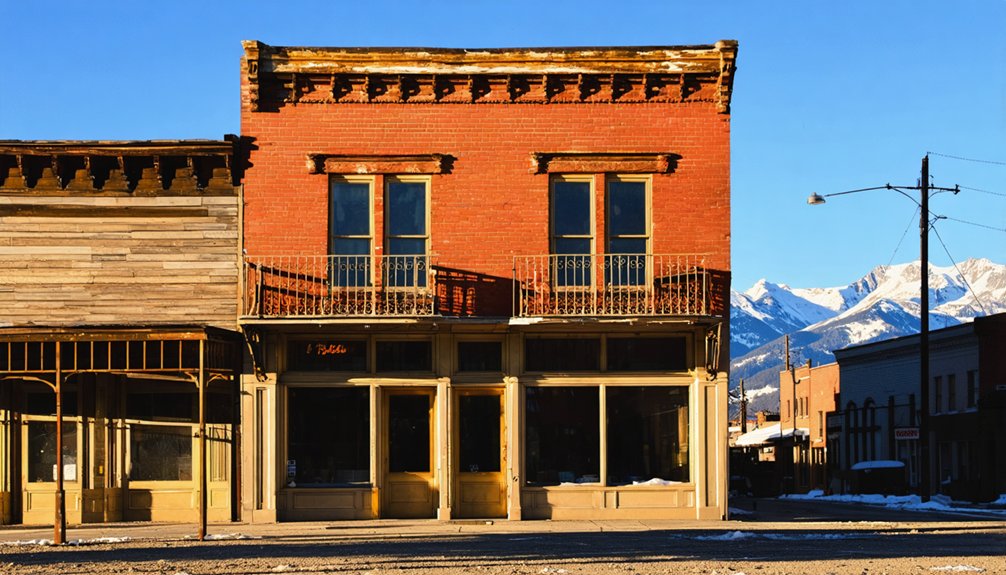

- The Victorian commercial facades lining main street, testifying to mining boom prosperity

- The brick-and-limestone Town Hall (1908), restored after fire and honored with a National Preservation Award

- The Mayflower Mill, operating until 1991, representing industrial-scale mineral processing heritage

- The all-volunteer historical society transformed the 1908 Miners Union Hospital into a community space

- Unemployed miners were hired for the award-winning town hall restoration

- The Animas Forks stabilization received $330,000 in grants

- Multiple National Historic Landmark designations bring thousands of tourists annually

- http://www.watsonswander.com/2014/silverton-mountains-mines-ghost-towns/

- https://www.legendsofamerica.com/silverton-colorado/

- https://www.uncovercolorado.com/ghost-towns/animas-forks/

- https://www.uniquetravelphoto.com/animas-forks-ghost-town-in-silverton-colorado/

- https://www.silvertoncolorado.com/history-of-silverton

- https://www.durango.com/colorado-ghost-towns/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silverton

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uHfVU7833vE

- https://www.irunfar.com/a-totally-serious-history-of-silverton-colorado

- https://josepholbrych.com/2023/07/31/a-portrait-of-silverton-colorado-the-past-present-and-future-of-a-colorado-mining-town/

When the D&RGW attempted abandonment, regulatory intervention saved this historic treasure, ultimately leading to its preservation as a heritage railway that continues connecting visitors with Silverton’s past.

The Silver Crash of 1893: Economic Upheaval and Exodus

When President Cleveland signed the repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act in 1893, few could have predicted the devastating cascade of economic failures that would transform Silverton and countless other mining communities across Colorado.

As silver prices plummeted from 83 to 62 cents per ounce, Silverton’s one-dimensional economy crumbled. The economic consequences rippled through every aspect of life—banks collapsed, property values evaporated, and businesses shuttered. Panic withdrawals from financial institutions led to numerous bank failures and residents lost their life savings overnight.

Buildings that once commanded thousands sold for hundreds, standing vacant for decades afterward. Labor struggles intensified as mine owners slashed wages despite the growing pool of desperate workers.

You’d have witnessed entire families packing their belongings, abandoning homes they could no longer afford. The town’s population hemorrhaged as unemployed miners sought opportunities elsewhere, leaving behind a shell of Silverton’s former prosperity—a prelude to its eventual ghost town status.

Animas Forks: Life at 11,000 Feet

While Silverton proper struggled with economic collapse following the silver crash, another remarkable settlement perched high above the valleys faced challenges beyond mere market fluctuations.

Animas Forks, situated at over 11,000 feet, represents one of North America’s highest mining communities where residents braved extreme conditions for prosperity.

Perched at dizzying heights, these hardy souls gambled their lives against nature for the promise of silver riches.

When you visit this well-preserved ghost town, you’ll discover:

This remote outpost, requiring 4×4 vehicles to access, peaked at 450 residents before harsh conditions and economic downturns transformed it into the ghost town you can explore today.

Surviving the Elements: Winter Isolation and Mountain Challenges

You’ll find it hard to imagine how Silverton’s residents survived winters with 175 inches of snowfall that sometimes buried entire buildings to their eaves.

During the most extreme weather, locals tunneled beneath massive snow drifts to move between structures, while using kicksleds to navigate the packed streets when venturing outside.

Miners and their families typically migrated from higher elevations (11,200 feet) down to Silverton each fall, creating a seasonal rhythm of population flux that defined life in these harsh mountain communities.

Snowbound Mountain Community

Perched at a breathtaking 9,318 feet elevation, Silverton stands as the highest incorporated town in San Juan County, where winter transforms this remote mountain community into a truly isolated outpost.

You’ll find the rugged San Juan Mountains surrounding this bastion of mountain resilience, where annual snowfall often exceeds 300 inches, cutting off easy access via Highway 550 due to frequent avalanches and closures.

The winter community of 600-700 year-round residents has adapted to this magnificent isolation through:

Despite these challenges, Silvertonians embrace their freedom in this snowbound sanctuary rather than flee it.

Survival Through Tunneling

Throughout the harshest winter months, Silverton’s predecessor community of Animas Forks developed an extraordinary survival technique that defined mountain resilience—elaborate snow tunneling.

When blizzards buried the town under 25-foot drifts, residents grabbed shovels and carved narrow passageways between buildings. Tunnel construction was grueling work at high altitude, requiring constant maintenance against collapse. Residents reinforced walls with timber while keeping passages narrow for structural integrity.

During the infamous 23-day blizzard of 1884, these tunnels became lifelines for accessing food, checking on neighbors, and maintaining community resilience. You can imagine the psychological toll of this confined existence—rationing supplies, battling hypoxia, and fearing avalanches.

Yet this communal practice guaranteed survival when outside help was impossible, creating a winter network that preserved both lives and social bonds.

Seasonal Migration Patterns

While snow tunneling allowed some residents to endure Animas Forks’ brutal winters, most locals opted for a more practical solution: seasonal migration. This migration strategy became vital for survival at 11,200 feet, where blizzards could last 23 days and snowdrifts reached 25 feet.

You’d find community resilience on display as families prepared for their annual journey to Silverton, where conditions were comparatively milder.

The migration cycle followed predictable patterns:

This pattern of exodus and return characterized life in the San Juan Mountains, ultimately contributing to Animas Forks’ ghost town status by the 1920s as mining declined.

The Wild Side of Silverton: Blair Street’s Notorious Past

As you wander down Blair Street today, you’re treading on the same path where thousands of miners once sought relief from their grueling work in Silverton’s notorious entertainment district.

Named after Thomas Blair, an original prospector who helped plat the town in 1871, this strip quickly evolved into Silverton’s red-light district.

Blair Street’s evolution from frontier road to vice center happened rapidly as the mining boom attracted saloons, gambling halls, and brothels.

The raw frontier transformed overnight, as whiskey, cards, and women of negotiable virtue followed the silver rush.

Notorious figures like “Jew Fanny” became legendary madams, while establishments like 557 Blair Street (now Natalia’s Restaurant) operated as bordelloes.

The community maintained an unspoken boundary along Greene Street—respectable businesses on one side, debauchery on the other.

Though authorities occasionally cracked down, they mostly collected fines from the 117 “lewd women” who kept the miners entertained.

Architectural Legacy: Historic Buildings That Withstood Time

From Blair Street’s saloons and brothels to the enduring architecture that defines Silverton today, the town’s history remains etched in its buildings.

You’ll find remarkable examples of architectural significance throughout this mining community, where preservation efforts have saved structures from nature’s harsh embrace.

The historical preservation of Silverton’s built environment includes:

When you explore these buildings, you’re walking through living monuments to the resilience, ingenuity, and ambition that defined Colorado’s mining era.

Beyond the Mines: Daily Life in a Rocky Mountain Boomtown

Beneath the gritty exterior of Silverton’s mining operations thrived a complex social tapestry that you’d recognize as surprisingly metropolitan for a remote mountain settlement.

At its peak, over 3,000 residents supported a vibrant ecosystem of businesses—29 saloons, numerous newspapers, banks, and laundries—all nestled in this mountain enclave.

Imagine 3,000 souls sustaining a thriving mountain community—complete with dozens of saloons, multiple newspapers, and all the amenities of civilization.

You’d find cultural exchange flourishing after the Denver & Rio Grande Railway’s arrival in 1882, connecting isolated miners to the outside world.

Community engagement centered around Blair Street’s notorious red-light district, where saloons and brothels operated alongside legitimate businesses, creating a unique social landscape.

Despite natural disasters and economic volatility, Silvertonians demonstrated remarkable resilience.

When metal prices plummeted, they adapted, ultimately transforming their mining heritage into a tourism draw that continues attracting freedom-seeking visitors to these picturesque mountainsides today.

Preserving the Past: From Abandonment to Heritage Tourism

Silverton’s journey from booming mining center to ghost town wasn’t the end of its story, but rather the beginning of an extraordinary preservation saga.

Without a historic preservation ordinance until recently, the town relied on passionate community engagement through organizations like the San Juan County Historical Society, which has secured over $12 million in grant money.

The town’s preservation efforts showcase remarkable funding sources and local ingenuity:

This heritage tourism now forms the economic backbone of Silverton, proving that preservation isn’t just about history—it’s about creating sustainable futures for mountain communities.

Frequently Asked Questions

Did Any Famous Outlaws or Celebrities Visit Silverton During Its Heyday?

Despite a million tall tales, you won’t find evidence of famous outlaws or celebrity visits in Silverton’s heyday. Records show the town’s isolation limited notable guests to miners and businessmen.

What Indigenous Artifacts Remain From Pre-Mining Silverton?

You’ll find few documented indigenous artifacts from pre-mining Silverton. Local museums preserve some Ute tools and pottery, but indigenous history suffered as mining expansion erased much cultural evidence from the landscape.

How Did Children Receive Education in These Remote Mining Towns?

You’d find education centered around brick schoolhouse structures, often taught by local teachers while facing isolation, harsh winters, and economic fluctuations that directly impacted curriculum quality and facility maintenance.

What Happened to Silverton During Prohibition?

You’d have witnessed Silverton’s transformation as Prohibition impacts shuttered saloons, forcing them to become soda fountains or theaters while bootlegging activities continued underground, evidenced by hidden liquor bottle caches found years later.

Were There Any Major Mining Disasters in Silverton’s History?

Yes, you’ll discover Silverton suffered numerous mining accidents, particularly the 2015 Gold King Mine spill that released toxic wastewater. Lax safety regulations throughout history contributed to disasters affecting Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah.