You’ll find Thurber’s ghost town remains in north-central Texas, where a coal mining empire once flourished from 1886 to 1926. This company-controlled town, surrounded by barbed wire and armed guards, housed up to 10,000 residents from 20 different nationalities who worked the mines. After successful unionization in 1903, Thurber became America’s first 100% union shop city, but the shift from coal to oil power ultimately sealed its fate. The preserved structures tell a compelling story of industrial Texas’s transformation.

Key Takeaways

- Thurber transformed from a thriving coal mining town of 10,000 residents in the early 1900s to a ghost town by 1931.

- The town’s decline occurred when Texas industries switched from coal to oil power, making coal mining operations obsolete.

- Only the smokestack, cemetery, and a few historic buildings remain from what was once Texas’s first company town.

- The W.K. Gordon Center now preserves Thurber’s history through exhibits and educational programs about the ghost town.

- The abandoned town symbolizes the dramatic impact of industrial change, as the entire community vanished when mining operations ceased.

The Birth of a Coal Mining Empire

While many Texas towns emerged from cattle drives or oil discoveries, Thurber’s story began with coal in 1886 when William and Harvey Johnson established their first mining operation.

After purchasing the Pedro Herrera survey property, they quickly developed mineshaft No. 1, which became operational by December of that year.

The Texas and Pacific Railway‘s decision to construct a spur line to Thurber proved essential for the town’s rapid growth.

You’ll find that this strategic partnership helped transform the isolated mining camp into a thriving industrial center.

The economic impact was immediate, as coal mining operations expanded to meet the railway’s growing demands.

The Johnsons’ vision attracted a diverse workforce from across America, Italy, and Poland, laying the foundation for what would become one of Texas’s most significant mining communities.

By the height of its success, Thurber had grown into a bustling town of 8,000 to 10,000 residents.

Financial troubles in 1888 led to the sale of the company to Col. R.D. Hunter, who renamed it the Texas and Pacific Coal Company.

Life in a Company-Controlled Town

In Thurber, you’d find your entire life controlled by the Texas and Pacific Coal Company, which owned every building and business in town.

You couldn’t operate an independent enterprise, and company script served as the only accepted currency for purchases at company-owned stores.

Your access to the town itself was restricted, as only company employees, their families, and select professionals like teachers and clergy were permitted to live within its boundaries. The company even fenced off property to maintain strict control over its workforce. The town’s thriving community included a diverse population of nearly 20 nationalities living and working together.

Daily Control Measures

Life in Thurber operated under the Texas & Pacific Coal Company‘s complete control, with the company owning every building, utility, and service in town.

You’d find yourself living within a barbed-wire perimeter patrolled by armed guards, who strictly controlled who entered and left. The company’s surveillance measures extended to every aspect of daily life, from where you could shop to how you spent your wages.

You couldn’t escape the company’s economic grip since they paid you in script only redeemable at their stores. Steam whistles marked every hour of your workday, dictating when to wake, eat, and rest.

The community isolation was deliberate, with T&P recruiting workers from 18 different nationalities to prevent union solidarity. Miners earned an average of $54 per month while working in the dangerous coal mines.

You’d discover that even your neighbors were strategically placed, as the company maintained control by limiting communication and cooperation between ethnic groups.

Community Under Lock

The Texas & Pacific Coal Company’s iron grip on Thurber extended far beyond simple workplace control, creating a completely enclosed community where every aspect of daily life fell under corporate oversight.

Inside Thurber’s fenced perimeter, you’d find yourself immersed in a tightly controlled social experiment where community dynamics were deliberately manipulated to maintain order. The company’s strategy of social isolation guaranteed complete dependence on their authority.

- You couldn’t own property or operate independent businesses.

- Your wages came as company scrip, forcing you to shop at their store.

- You needed company approval for social gatherings and cultural events.

- Your neighbors were strategically segregated by ethnicity to prevent unified resistance.

Living in Thurber meant surrendering your autonomy to a system designed to monitor, control, and profit from every aspect of your existence.

Immigrant Stories and Cultural Mosaic

The immigrant resilience manifested in various ways.

When Thurber’s mines closed between 1921-1933, displaced families adapted by relocating to Illinois, New Mexico, and California.

Before the decline, immigrants had established vibrant communities with their own churches, social clubs, and businesses.

Polish miners earned one dollar per ton working in challenging conditions to support their families and community.

The eighteen ethnic groups created a diverse cultural tapestry that defined Thurber’s unique social character.

St. James Catholic Church served as a cultural anchor, while fraternal organizations fostered bonds across ethnic lines.

Power, Control, and Labor Struggles

You’ll find that the Texas and Pacific Coal Company maintained an oppressive grip over Thurber through physical barriers like barbed wire fences and strict control of worker movement.

The company’s efforts to suppress union activity included calling in Texas Rangers during an 1898 strike and attempting to restrict workers’ ability to organize.

Before the successful unionization in 1903, management’s tyrannical tactics created an environment of extreme tension between workers and company leadership, with rising threats against management reflecting the depth of labor conflict. The successful strike by miners in 1903 involved 1,200 workers and finally led to improved conditions.

The United Mine Workers union grew rapidly after the victory, with the town becoming a 100% union shop city under C.W. Woodman’s leadership.

Company’s Iron Grip

While many company towns exerted control over their workers, Thurber stands out as an extreme example of corporate dominion under the Texas and Pacific Coal Company’s iron grip.

The company created complete social isolation by fencing off the entire mining area and establishing total company dependence through their extensive town infrastructure.

- You’d find every aspect of life controlled by TPCC – from the houses you lived in to the stores where you shopped, with company tokens as your only currency.

- Your children would attend company schools, shaping their worldview from an early age.

- The company deliberately recruited workers from 18 different nationalities to prevent unified resistance.

- You couldn’t escape their influence, as they owned everything from utilities to entertainment venues, creating an inescapable web of control.

Union Suppression Methods

Under TPCC’s iron grip, union suppression became a sophisticated operation combining state power, economic pressure, and social division.

You’ll find the Texas Rangers deployed in 1903 to protect company interests, while Governor Sayers’ visit in 1902 demonstrated high-level political backing against union resistance.

The company’s economic manipulation was far-reaching. They controlled housing, stores, and essential services, creating total dependency.

When workers organized, they’d face not just their employer but an entire system designed to crush dissent. The company expertly exploited racial and ethnic divisions among the diverse workforce – Italians (52%), Poles (12%), Mexicans (11%), African-Americans (11%), and Anglo-Americans (9%) – to hinder unified labor action.

They even limited education and perpetuated child labor, ensuring generational control over their workforce.

Worker Control Tactics

After gaining control of Thurber’s mines in 1888, the Texas and Pacific Coal Company established an elaborate system of workforce control by constructing a completely self-contained company town.

You’d find every aspect of life controlled through company-owned housing, stores, utilities, and amenities. The company’s worker exploitation strategy centered on recruiting a diverse immigrant workforce from eighteen nationalities, deliberately creating labor fragmentation through language barriers and cultural differences.

- Company fenced the entire mining area to restrict worker movement and access

- Control extended through monopolization of housing, schools, churches, and stores

- Strategic recruitment of non-English speaking immigrants limited collective resistance

- Exclusion of union activists from employment enforced compliance and weakened organizing

These tactics maintained company dominance until unified union resistance emerged in 1903.

The Golden Age of Texas Coal

During the early 1900s, Thurber emerged as Texas’s premier coal-mining center, establishing itself as a cornerstone of the state’s industrial revolution.

You’d find a thriving community of 8,000-10,000 residents at its peak around 1918-1920, with advanced mining techniques powering the region’s railroad locomotives.

The workforce, comprised of immigrants from across Europe and African Americans, built one of America’s first fully unionized mining towns by 1907.

The United Mine Workers’ influence secured essential labor rights, while the town’s diverse cultural makeup created a unique industrial community.

Under the Texas & Pacific Coal Company’s management, Thurber’s production reached unprecedented levels, fueling the expanding railroad network and establishing itself as the state’s principal bituminous coal producer during this golden age.

Industrial Innovation and Brick Manufacturing

While coal mining drove Thurber’s initial growth, the town’s brick manufacturing enterprise emerged as an equally innovative industrial venture in 1897.

You’ll find that Thurber’s industrial adaptation transformed mining waste into valuable construction materials, establishing the best-equipped brick plant west of the Mississippi. The operation’s brick durability earned national recognition, with their vitrified paving bricks leading the market.

Here’s what made Thurber’s brick production remarkable:

- Efficient use of local shale clay and non-commercial pea coal as fuel

- Twenty-four continuously rotating kilns producing 80,000 bricks daily

- Superior quality proven through prestigious projects like Dallas Opera House

- Hundreds of miles of Texas highways paved with Thurber bricks

The enterprise’s success extended beyond Texas, supporting infrastructure development across multiple states during the early 1900s.

Daily Life Behind the Barbed Wire

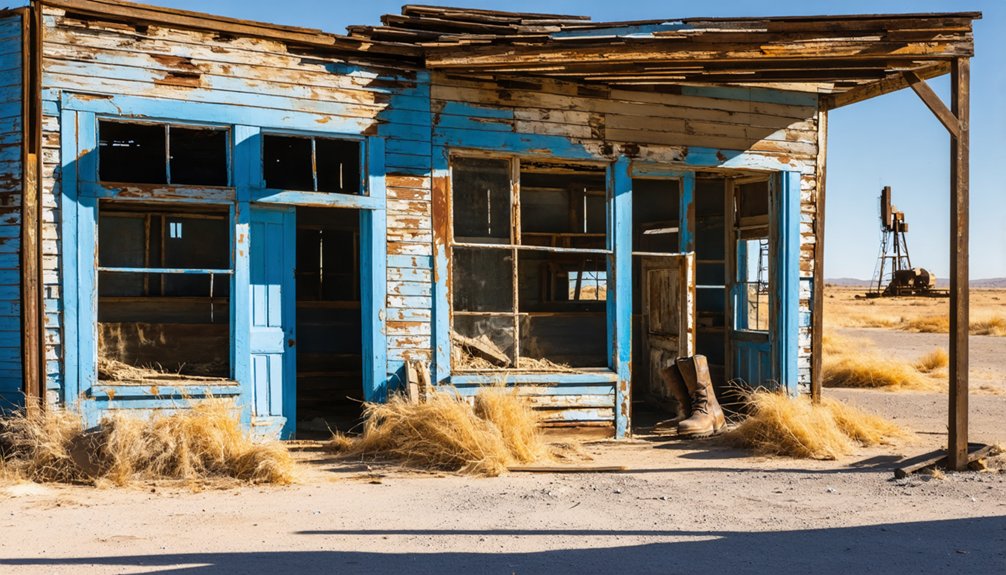

Behind Thurber’s four-strand barbed wire fence lay a tightly controlled company town where armed guards patrolled 900 acres of territory, monitoring the movements of its diverse workforce.

You’d find yourself among eighteen different nationalities, speaking a babel of languages while enduring daily struggles in the mines. For 10 to 12 hours a day, six days a week, you’d work prone in coal seams barely three feet thick, swinging pickaxes for $1.05 per ton.

Steam whistles would dictate your schedule, from dawn until dusk. While you’d enjoy modern amenities like electricity and running water at home, you couldn’t escape the company’s watchful eye.

Modern comforts couldn’t mask the iron grip of company control, as whistles commanded every hour of miners’ waking lives.

The barbed wire kept labor organizers out and guaranteed you remained dependent on company-owned stores, churches, and saloons for all your needs.

The Decline and Abandonment

You’ll find that Thurber’s economic collapse stemmed from multiple, compounding factors: the railroad’s shift from coal to oil-based fuel, the rise of asphalt over paving bricks, and persistent labor unrest that strained company profits.

The Texas and Pacific Coal Company’s failure to adapt its business model beyond coal mining and brick manufacturing left the town vulnerable when these industries became obsolete in the 1920s.

Factors Behind Economic Collapse

Despite its early prosperity, Thurber’s economic collapse stemmed from three interconnected factors that proved devastating to the company town’s survival.

You’ll find that economic dependency on a single coal company left Thurber vulnerable, while labor exploitation through company scripts and low wages created an unstable workforce.

The fatal blow came when railroads switched from coal to oil fuel, destroying Thurber’s primary market.

- The Texas and Pacific Coal Company’s total control meant residents couldn’t build alternative economic foundations.

- Labor unrest peaked in 1921 when miners struck against harsh working conditions.

- The rise of petroleum drastically reduced demand for Thurber’s coal and brick products.

- The Great Depression accelerated the decline by further shrinking already dwindling markets.

Last Residents Move Out

The decline of Thurber unfolded rapidly after coal mining operations ceased in 1926, marking the beginning of a mass exodus from the once-thriving company town.

By 1931, you’d have found only 270 families remaining, with that number dropping to 250 the following year.

The last days of Thurber saw the systematic shutdown of essential services.

You’d have witnessed the schools closing by 1935, forcing children to attend classes in neighboring towns.

The post office’s final farewell came in November 1936, replaced by rural mail routes.

The company stores cleared their remaining inventory by July 1933, leaving residents without local retail options.

As employment opportunities vanished and amenities disappeared through the late 1930s, the few remaining residents had no choice but to relocate, transforming Thurber into a ghost town.

Standing Sentinels: Preserved Structures

Scattered remnants of Thurber’s industrial past stand preserved within the town’s officially designated historic district, where ten major original buildings showcase the once-thriving company town’s architectural legacy.

Today, you’ll find preserved architecture ranging from company offices to a miner’s residence, each structure telling its own story of historical significance through original details like barber shop tiles and distinctive brickwork.

- The W.K. Gordon Center displays relocated treasures, including the Catholic Church

- Original foundation outlines reveal the town’s sophisticated infrastructure

- Multi-story facilities demonstrate the company’s substantial investment

- Immigrant influences from 20+ countries shaped unique architectural features

You can explore these standing sentinels yourself, just 70 miles west of Fort Worth, where two restaurants now operate among the carefully preserved ruins.

A Monument to Industrial Texas

Once America’s largest company town in Texas, Thurber stands as a tribute to the state’s essential shift from coal to oil power during the early 20th century.

You’ll find that Thurber’s legacy extends beyond its coal mines, representing a pivotal chapter in Texas industrial heritage when the town produced over 1.2 million tons of coal by 1913.

At its height, you could’ve witnessed a remarkably diverse workforce of 8,000 to 10,000 people, including immigrants from across Europe and Mexico, powering both coal mining and brick-making operations.

The town’s industrial might declined after oil’s discovery in nearby Ranger, leading to mine closures in 1926.

Today, Thurber serves as a symbol of industrial transformation, preserved through institutions like the W.K. Gordon Center, where you can explore this vital period in Texas’s economic evolution.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Happened to the Residents’ Belongings When They Abandoned Thurber?

Your abandoned belongings were either hastily sold, taken with you, or left behind during the rapid town closure, scattering resident memories as buildings were dismantled and infrastructure removed.

Are There Any Documented Ghost Stories or Paranormal Activities in Thurber?

While dozens of anecdotal stories exist, you’ll find no officially documented ghost sightings. Local tales center on haunted locations like the mining complex and opera house, stemming from the town’s labor struggles.

How Much Did Miners Typically Earn per Day in Thurber?

You’d have earned about $1.57 per day as a miner, mining roughly one ton of coal daily. Mining wages barely covered your expenses since you’d need to purchase your own tools, costing up to $2.00.

What Became of the Company’s Financial Assets After Thurber’s Closure?

After closing the $2 million brick plant, you’d see financial liquidation directing assets to Fort Worth offices, with remaining capital distributed through equipment sales, store inventory liquidation, and corporate consolidation.

Did Any Original Thurber Families Continue Living Nearby After the Shutdown?

You’ll find little evidence of Thurber descendants remaining in nearby communities after 1936. Most families dispersed when schools closed, services ended, and employment disappeared during the town’s final shutdown.

References

- https://www.themoonlitroad.com/ghost-town-thurber-texas/

- https://jemully.com/lively-little-ghost-town-thurber-texas/

- https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/thurber-tx

- https://www.tarleton.edu/gordoncenter/thurber-history/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=phjUE19A8HM

- https://www.texasescapes.com/FEATURES/Thurber_Texas/Thurber_Texas_ghosttown.htm

- https://www.tarleton.edu/library/crosstimbers/collections/thurbercollection/thn00014/

- https://www.texasalmanac.com/articles/thurber-texas-coal-town

- https://www.thurbersmokestack.com/historical-timeline-of-thurber-texa

- http://www.thurbertexas.com/history/strike.html