You’ll find Union Valley, Texas as a poignant example of frontier settlement decline. Founded in the 1860s, this once-thriving community reached its peak in 1892 with 300 residents, three general stores, and a bustling commercial district centered around Harriet Smith Beaty’s 1872 log schoolhouse. The railroad’s bypass in 1906 triggered the town’s downfall, leaving only 25 residents by the 1980s. Today, historical markers and a cemetery near FM 1681 preserve compelling stories of pioneer resilience.

Key Takeaways

- Union Valley, Texas flourished as a frontier settlement in the 1860s, reaching 300 residents by 1892 before declining to ghost town status.

- The 1906 railroad bypass triggered the town’s downfall, leading to business closures and population decline to just 25 residents by 1980s.

- Historical markers on FM 1681 commemorate the town’s past, including the 1877 schoolhouse that served multiple community functions.

- The maintained cemetery contains graves of diverse immigrants and Jane Bowen, first wife of outlaw John Wesley Hardin.

- Originally centered around Harriet Smith Beaty’s 1872 log schoolhouse, the town became a hub with stores, mills, and cotton gins.

The Rise of a Texas Frontier Settlement

During the 1860s, Union Valley emerged as a resilient frontier settlement in Texas, establishing itself around a crucial log schoolhouse built by Harriet Smith Beaty in 1872.

In rugged 1860s Texas, Union Valley grew from humble beginnings, centering around Harriet Smith Beaty’s pioneering log schoolhouse.

Like the Fisher-Miller Grant, the area played a vital role in early Texas settlement patterns and development.

You’ll find that despite frontier challenges, the community quickly adapted, with pioneering families like the Burnsides, Cones, and Creeches leading agricultural innovations in the region.

The settlement’s strategic location near the Wilson/Gonzales County line fostered growth, as you’d have witnessed the establishment of essential services catering to local farmers.

By 1883, a post office anchored the community, transforming Union Valley into a vibrant hub.

The town’s development accelerated through the 1890s, featuring three general stores, a Methodist church, and critical agricultural infrastructure including a mill and cotton gin, showcasing the settlers’ determination to build a thriving frontier economy.

By 1903, education remained a cornerstone of the community with a two-teacher school serving sixty-five students.

Life in Union Valley’s Golden Age

As you walk through Union Valley during its 1890s peak, you’d find a bustling frontier settlement anchored by three general stores, a Methodist church, and essential services like the blacksmith shop and mill.

The town’s commercial district served as both an economic and social hub, where farmers brought their cotton for processing while townspeople gathered to exchange news at S.E. Johnson’s store or the local saloon. The spirit of community and collaboration was evident in how residents worked together to maintain the town’s prosperity. With a population of 300 recorded in 1892, Union Valley was thriving as a center of rural commerce.

The two-room schoolhouse doubled as a Masonic hall and courtroom, exemplifying how frontier communities maximized their limited facilities to support both education and civic functions.

Community Landmarks and Commerce

Three prominent general stores anchored Union Valley’s commercial district during its golden age in the 1890s, establishing the town as an essential economic hub.

You’d have found a bustling downtown where merchants like Johnson and Magee served the community’s daily needs. The commercial evolution of Union Valley included important services like a blacksmith shop, mill, and cotton gin that supported the agricultural backbone of the region. The cotton gin was first established by Sam Matthis and Bill Stamps to serve the area’s growing agricultural needs.

Key landmarks defined the town’s character, with Harriet Smith Beaty’s 1872 log schoolhouse standing as evidence of the community’s commitment to education.

The Methodist church and local saloon served as crucial social gathering spots, while the 1883 post office marked Union Valley’s significance in regional commerce and communication before the railroad’s bypass altered its trajectory.

Daily Rural Social Life

Life in Union Valley flowed through a rich tapestry of social interactions centered around key community landmarks in the 1890s.

You’d find residents gathering at the Methodist church for spiritual guidance and fellowship, while the two-room schoolhouse served dual purposes as both an educational facility and community meeting space.

The town’s social hubs included the general stores, blacksmith shops, and saloons, where you’d exchange news and conduct business with your neighbors.

Community gatherings regularly brought together about 65 school children and their families, alongside prominent business owners like the Burnsides, Dunns, and Pattersons.

Whether you were trading at the cotton gin, attending Masonic meetings, or participating in seasonal celebrations, these daily interactions strengthened the bonds between Union Valley’s residents and neighboring communities like Albuquerque and Nockenut.

The townsfolk’s commitment to preserving their heritage through local history preservation helped maintain their strong sense of community identity.

Educational Heritage and Community Learning

Education played a central role in Union Valley’s community identity from its earliest days, beginning with Harriet Smith Beaty’s donation of a log schoolhouse in 1872.

Through educational preservation efforts, this modest structure evolved into a two-room schoolhouse by 1903, serving 65 students under two teachers’ guidance.

You’ll find that the school buildings served multiple functions beyond traditional learning. As a hub for community outreach, these facilities hosted church services, Masonic meetings, and local court sessions. Like many rural Texas communities including Loyal Valley settlers, the town maintained strong German cultural traditions through various educational programs.

Even after the post office changed its name to Union in 1900, the school maintained the original Union Valley name, preserving the community’s heritage.

This multifunctional approach to education reflected both resource limitations and the strong civic spirit that defined rural Texas settlements until the town’s decline following the 1906 railroad bypass.

Religious and Social Gatherings

While Union Valley’s social fabric centered on multiple institutions, the Methodist church emerged as the town’s primary gathering place in the late 19th century.

You’d find residents congregating there not just for worship, but for a variety of church events and community rituals that strengthened local bonds.

The town’s resourceful use of space was evident in its multi-purpose buildings.

The 1877 schoolhouse served as a Masonic hall, church, and courtroom, maximizing the limited facilities available to residents.

Community rituals often extended to the Union Valley cemetery, where memorial services and remembrance gatherings reinforced family ties.

Even after the town’s decline following the 1906 railroad bypass, social gatherings continued, though less frequently, preserving the community’s shared heritage and religious traditions.

The Impact of Railroad Bypass and Decline

In 1906, the Galveston, Harrisburg & San Antonio Railroad’s strategic bypass of Union Valley dealt a devastating blow to the town’s economic significance. The railroad evolution left this small Texas settlement in economic isolation, cutting off crucial transportation links that previously sustained local commerce and agriculture. Similar to other Texas communities like Hearne that relied on the International & Great Northern railroad, Union Valley’s fate was inextricably linked to rail transportation decisions. The Great San Francisco earthquake of that same year had already strained railroad operations nationwide, compounding the challenges faced by small railroad-dependent towns.

- The bypass forced the closure of essential businesses including stores, cotton gins, saloons, and trade shops.

- Population declined sharply, never exceeding 50 residents and dwindling to just 25 by the 1980s.

- Loss of rail connectivity prevented the town’s integration into expanding economic networks of early 20th century Texas.

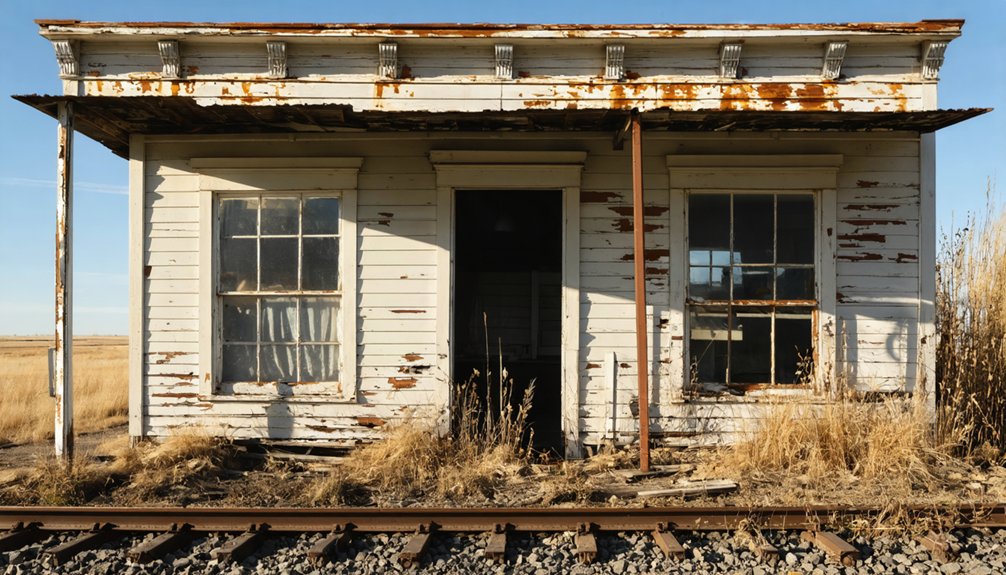

You’ll find that Union Valley’s transformation into a ghost town exemplifies how strategic railroad decisions could determine a community’s fate, as younger generations sought opportunities in better-connected towns, leaving aging infrastructure and diminished services behind.

Historical Landmarks and Cemetery Tales

Though Union Valley’s economic significance faded with the railroad’s bypass, the town’s historical landmarks still tell a rich story of its once-thriving community.

Progress bypassed Union Valley, but its weathered landmarks whisper tales of a community that once bustled with life and commerce.

You’ll find a historical marker installed in 1972 off FM 1681, standing as evidence to landmark preservation efforts. Like other ghost towns such as Belle Plain College, the 1877 frame schoolhouse served multiple roles as a Masonic hall, church, and courthouse, embodying the resourcefulness of early Texas settlers.

The Union Valley cemetery, with its weathered iron fencing and headstones, holds secrets of the region’s diverse past. Among the graves, you’ll discover the final resting places of immigrants from Poland, Italy, Britain, and Ireland.

Local ghost stories often center around the cemetery and the Mound Creek burial ground near Nockenut, where Jane Bowen, John Wesley Hardin’s first wife, lies buried.

Modern-Day Remnants and Rural Legacy

You’ll find two official Texas historical markers standing as silent sentinels at Union Valley’s original site, marking its significance in Wilson County’s past.

The cemetery, still maintained and accessible today, tells poignant stories through its headstones, including that of Jane Bowen, wife of notorious outlaw John Wesley Hardin.

These physical remnants, along with scattered building foundations, offer tangible connections to the once-thriving rural community that has since transformed into a quiet agricultural landscape with just 22 residents in nearby Union.

Historical Markers Today

Modern visitors to Union Valley’s historic site will find a solitary 18-by-28-inch marker at the intersection of FM 1681 and County Highway 449, standing as the primary physical remnant of this once-thriving community.

Through historical preservation efforts, the Texas Historical Commission and Wilson County Historical Society maintain detailed records of this marker, ensuring its legacy endures for future generations.

- The marker serves as an educational outreach tool, documenting the town’s 1860s settlement, civic development, and eventual decline.

- You’ll find the marker on public land, allowing unrestricted access for research and cultural tourism.

- The site continues to host Union Valley Homecoming Association gatherings, preserving community connections.

The marker’s text captures the essence of rural Texas life, from early settlers to business owners, providing invaluable insights into the region’s social and economic history.

Cemetery’s Silent Stories

Located five miles northwest of Nixon, Texas, the Union Valley Cemetery stands as a poignant tribute to the area’s vanished frontier community.

You’ll find over 500 memorial records here, with weathered headstones that reveal 19th and early 20th-century burial customs. The grave inscriptions tell personal stories of settlers, Confederate veterans, and pioneer families who shaped this rural landscape.

The cemetery symbolism extends beyond mere markers – it’s a reflection of the region’s cultural legacy. As one of the few remaining physical artifacts from Union Valley’s ghost town era, the site’s cemetery serves as a silent storyteller of the community’s rise and decline.

While natural degradation threatens some stones, ongoing documentation efforts help preserve the collective history of this significant rural Texas burial ground.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Happened to the Families Who Left Union Valley After 1906?

You’d be amazed how family migrations scattered these folks to railroad-connected towns and cities, as economic factors pushed them toward better opportunities. They rebuilt their lives in more prosperous Texas communities.

Are There Any Surviving Photographs of Union Valley’s Original Buildings?

You’ll find limited photographic evidence exists, primarily the original 1871 log schoolhouse in Laura Swiess’s family album and the 1927 school. Most historical preservation efforts focus on private collections.

What Crops Were Primarily Grown by Union Valley’s Farming Community?

Like waves across the prairie, you’d have seen cotton production dominating the landscape, with corn farming playing a crucial second role. Wheat, oats, and sorghum rounded out your main field crops.

Did Any Notable Outlaws or Historical Figures Visit Union Valley?

You won’t find documented outlaw sightings or historical visitors in this community. While John Wesley Hardin’s wife is buried nearby, there’s no evidence he or other notable figures ever visited.

What Native American Tribes Inhabited the Area Before Union Valley’s Settlement?

You’ll find the Caddo Indians were the primary inhabitants, leaving their tribal legacy through farming and trading. The Shawnee and Delaware also had cultural influence before being displaced by Texas settlers.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Union

- https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/union-valley-tx

- https://www.allacrosstexas.com/texas-ghost-town.php?city=Union+Valley

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ghost_towns_in_Texas

- https://www.wilcotx.gov/1635/Historical-Abandoned-Towns

- https://www.wilsoncountyhistory.org/talk-union-valley

- https://atlas.thc.texas.gov/Details/5493004865

- https://www.texasescapes.com/TOWNS/Texas-Ghost-Towns-8-South-Texas.htm

- https://www.texasescapes.com/SouthTexasTowns/Union-Valley-Texas.htm

- https://texashillcountry.com/loyal-valley-hill-country-ghost-town/